The Tin Sarcophagus Chapters 1,2,3,4

The Tin Sarcophagus Chapters 1,2,3,4

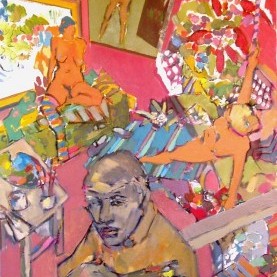

For thirty years the artist Pierre Bonnard's companion and muse remained the legendary 'Marthe', whom he had first seen in a Paris Street in 1893 and followed to the funeral parlour where she worked sewing artificial flowers onto wreaths. In 1918 he met shop-girl Renée Montchaty. He was fifty; she was eighteen. In 1923 Bonnard told Marthe he was leaving her to take Renée to Rome and planned to marry her on their return. He arrived back in Paris a month later in a state of nervous collapse. Within a month he had married Marthe, Three weeks after the marriage, Renée committed suicide What happened in Rome that August to change the direction of all their lives, is the subject of this novel.

60Historical fiction

Lynn Bushell (United Kingdom)

PARIS 1893

I sometimes wonder if our whole life isn’t just a random accident. Ten seconds either way and we'd have missed each other. There I was stuck in the middle of the rue du Bac, a horse-drawn cab on both sides, neither of the bastards willing to give way, steam coming from the horses’ nostrils and sparks flying from the cobbles. And then there’s the rain – the sort you only get in Paris. It’s a mean rain, sleety, with a chill that gets you right through to the bone.

He’s watching from the pavement opposite, as if all this is a performance that I’m putting on to liven up the morning. He could be a toff or somebody who only has one coat and sleeps in it – it’s hard to tell. He’s black from head to foot. I can remember thinking, ‘if I fall under the wheels of one of these cabs, this is who’ll be there to greet me on the other side. That, or he’ll be the undertaker.’

There’s a moment when it’s as if somebody has shouted ‘Stop!’ and everything and everybody on the street is frozen. Then he steps into the road and puts his hand up to the nearest cab. He walks in front of it and when he gets to me, he takes my arm. Up close, he’s scruffy, but there’s an expensive smell about him, as if he has washed first before putting on old clothes. He asks me where I’m going and I say ‘the dead house.’ He’s not sure he’s heard me right. 'I work there,' I say. 'I sew flowers on the wreaths.'

'You don’t regret it?’ he said later. ‘Are you sure you wouldn't rather be back sewing flowers onto wreaths?'

'It's not the sort of job you miss,' I told him.

PARIS 1917

She loves opening presents, getting her nail underneath the knot and easing it apart, unravelling it slowly, winding up the ribbon so that she can keep it for another time, then carefully unwrapping what's inside and smoothing out the paper, folding it in half and then in quarters, finally....

Snip. Marguerite has cut the string. Now nothing separates her from the contents but the flimsy paper wrapped around it, but she doesn't care what's in the box now.

'Well, go on,' says Margo. 'Open it.’

She glances up and in the look that passes momentarily between them, Renée feels the force of her desire and knows whatever Marguerite has bought her is a relic of it.

It's a signet ring. It isn't flashy – a plain setting with a blue stone in the centre of it – imitation sapphire. But it's not the sort of thing you'd pick up in the Marche aux Puces, which means that Marguerite has bought it from a jewellers. There is a label on the box that says as much. The ring is slotted with the jewel facing upwards on a satin-covered base that momentarily reminds her of the pillow underneath her father's head when he was lying in his coffin. She tries not to touch it when she takes the ring out.

‘Happy birthday.’ Marguerite is looking at her avidly.

'It's lovely,' Renee says. 'It must have cost an awful lot.' The shrug that Marguerite gives isn't quite as careless as it might be. Renée hesitates. She'd rather not give Marguerite the opportunity to put the ring on for her. She rotates it underneath the lamp to catch the light, then deftly slips it on the finger of her right hand.

Marguerite gives her a quick glance. 'Don't you want to wear it on the other finger?'

Renée looks at her: 'The middle finger, do you mean?'

'I mean the finger on the other hand.'

'But that would look as if I was engaged,' says Renée, frowning.

'It would look as if you were committed. After all, you are committed, aren't you? We've been living in this flat together for the past two years.'

'Yes, but I don’t see why I have to wear it on that finger. Does it matter?’

‘If it doesn’t matter, why can’t you just put it on the finger it was meant for?’

Renée doesn’t answer. There's a pause, then Marguerite gets up and quietly clears the table. 'Think about it, Renée.' She goes out into the kitchen.

Renée curls the twine around her index finger. There is not enough to be worth keeping but the ribbon circles it three times. She pulls it tight. Her finger reddens at the end and goes white at the base. She loosens it and blood flows back into the finger. Then she tightens it again. Her finger starts to throb. Her head begins to throb as well.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Should we keep the string?’

‘Whatever for? We’re not that hard up.’

Renée lets the string unravel. She would keep it anyway but Marguerite has scooped it up into her hand and thrown it on the fire.

As they climb into bed, she puts her cheek out for the statutory kiss and Renée pecks it. They lie rigidly, the space between them like a ditch they run the risk of falling into. That night is the first in eight days that there hasn't been an air-raid. Lying there awake with Marguerite beside her, both of them pretending they're asleep, it would be a relief to hear a bomb go off.

She holds her breath and listens. Tentatively she puts out her hand and lets her fingers rest on Marguerite's arm. Marguerite turns over slowly. Renée feels her breath against her face. It's like the inside of a cupboard, she thinks: dry and musty with a hint of lavender and mothballs. The dry lips are pressed against her forehead. She likes this, the fact that Marguerite's lips aren't wet like the swampy kisses she's received from men who've kissed her in the past.

‘That’s better,’ Margo murmurs, pulling her into the narrow space between them. She wraps one arm round her shoulder 'I’ll look after you,’ she whispers. ‘You'll be safe with me.'

Once, they had turned the bed into a bier and Marguerite had laid her out.

'You're not to move,' she said. 'Pretend you're dead.'

When Renée’s younger sister Emilie had died at two years old, she'd helped her mother dress the body in a white shift with a crown of lilies. Emilie had had her cheeks and lips rouged slightly. She looked healthier than she had ever looked in life. The faint smile on her face was almost smug, thought Renée.

'I shall have to wash your body and then dress you in a shift,' said Marguerite. 'No matter what I do, you're not to giggle. If you do, you'll spoil it.'

Renée lay completely still whilst Marguerite undid the buttons on her blouse and gently drew her arms out of the sleeves. She disengaged the buckle on her belt and eased the skirt over her thighs. Her hands moved up from Renée's ankles to her knees and one by one unlatched the garters on her stockings, rolling them back down towards her ankles and across the heel. She unlaced Renée's corset, opening it up, and Renée, who'd been trying not to giggle, parted her lips silently in order to facilitate her breathing. Marguerite leaned forward suddenly and kissed her passionately on the lips. She looped her hands round Renée's drawers and deftly drew them down over her thighs. As Renée lay pretending she was dead, it struck her that she'd never felt so much alive.

‘If you were ever to tell anybody – ANYBODY – what we did together, Renée, you would be shut out of Paradise forever. Do you understand?'

Although she rarely questioned anything that Margo told her, Renée wondered how you could remain in Paradise no matter what you did, as long as no one knew about it. She felt vaguely that if she were to confess her sins, she wouldn't be forgiven. Marguerite was right, perhaps. It wasn't what you did that counted, but how well you kept the secret.

He was a voyeur; no doubt about it. I’ve known plenty in my time. There are the creepy ones who look at you as they would if they came across an animal run over in the road. If they discovered it was still alive, if they could see its heart was beating, they’d move on; real life is a distraction. Then there are the others – and he’s one of them, who are obsessed with something that is never quite you. They’re the worst – the ones who don’t know what they’re looking for until they find it.

***

Reviews

The reviews for this submission haven't been published yet.

Sign in ›

Sign in ›